It is acknowledged that Australian Aboriginal culture is heavily spiritual and symbolic, but a growing body of evidence suggests that the indigenous belief system represents a deep knowledge of the sky and the motion of the bodies within it.

This knowledge was used not just as components in ceremonial events and stories, but for practical purposes, such as constructing calendars. And there may even be evidence for careful records and measurements.

Scientists at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) have presented the hypothesis that Aboriginal people – whose existence stretches back, unbroken, for more than 50,000 years – could have been the world’s first astronomers.

There are around 400 different indigenous cultures in Australia, and while their languages can be as different as Chinese is from Italian, most share the idea that the world was created in the ‘Dreaming’ by ancestral spirits who left their symbols all around. These symbols offer an understanding of the world and present the rules by which one must live.

Dreaming stories also display a significant understanding of astronomical occurrences, such as a solar eclipse being explained by the Warlpiri people as the Sun Woman obscured by the Moon Man as they make love (or by the Wirangu people, as they become husband and wife). This demonstrates a comprehension that eclipses were caused by a conjunction between the sun and moon moving on different paths across the sky, occasionally intersecting.

The use of the night sky as a calendar is demonstrated by the Boorong people’s knowledge that when Lyra, what they call the ‘Mallee-fowl’ constellation, appears (in March) that the fowl are about to build their nests and that when Lyra disappears (in October) the eggs are laid and ready to be collected.

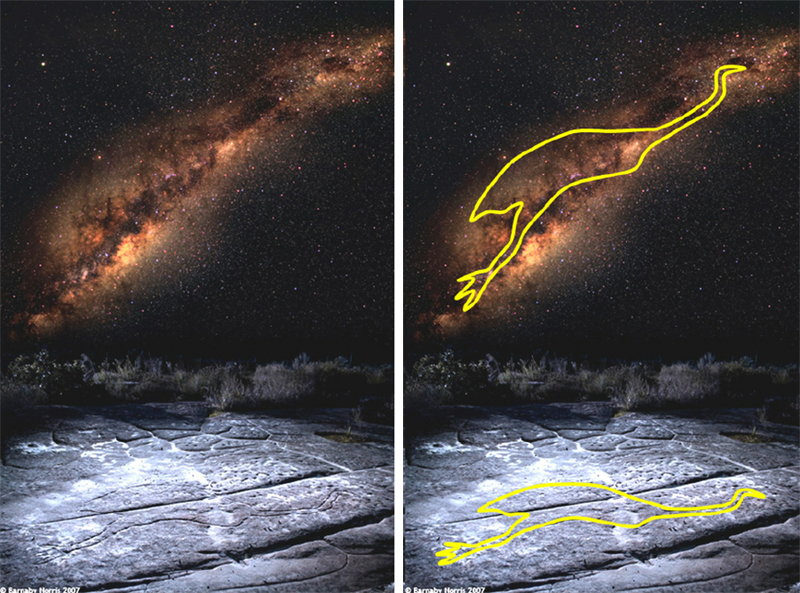

Kuringai Emu in the Sky, images by Barnaby Norris and Ray Norris

Coalsack Dark Nebula (within the Milky Way) is known to the Wardaman people as the head of the ‘Emu In The Sky’. The rest of its body falls to the left, seen as the darkness between the stars. In the Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, near Sydney, is an ancient Aboriginal rock engraving of the Emu In The Sky, oriented to line up with the nebula where it appears in the sky at the time when real-life emus are laying their eggs.

But perhaps the most important piece of evidence is a stone circle with astronomical significance, built on the traditional land of the Wathaurong people in Victoria, which could pre-date Stonehenge and Egypt’s pyramids.

Wurdi Youang, as the ancient sundial is known, is an egg-shaped ring of stones about 50m in diameter, with significant stones that line up with the positions of the sun at the equinoxes and solstices.

Wurdi Youang, image from Courier Mail

Macquarie University archaeo-astronomy student Duane Hamacher explains: “(There are) three large standing stones at one apex that mirror three mountains in the background. And at the apex of the other end, if you stand there and look down the centre of it, which is exactly east-west, you can see the equinox sitting over these three stones”.

“And if you look down the other side you see two rows that align to the solstices,” Mr Hamacher says.

“It is similar to Stonehenge, in some respects.”

CSIRO astrophysicist Professor Ray Norris said the precise alignment of the stones proved it was constructed to map the sun, possibly 10,000 years ago.

“This can’t be done by guesswork, it required very careful measurements. There’s enough evidence there that it looks like these people really did know about these special directions,” Professor Norris says.

“It is plausible (that it could date back) say, 10,000 years. That predates the Pyramids, Stonehenge, all that stuff.

“That would indeed make (Aboriginal people) the world’s first astronomers.”

Stonehenge is believed to be around 5,000 years old, while the Egyptian pyramids were built around 4,500 years ago.

While the people that built Wurdi Youang, and the stories of their culture, no longer exist – European settlers, and later Christian missionaries, destroyed and banned many indigenous cultures – Professor Norris says that the existence of the stone ring – which has remained undisturbed – is helping to drive a “tantalising” research field.

Professor Norris and colleagues are planning an Aboriginal astronomy conference and hope to establish a national working group on the subject.

The research could change people’s understanding of Aboriginal people and the development of advanced human thinking; an aspect of Aboriginal culture that was overlooked when white settlers took over the country in 1788.

It wasn’t until 1965 that Aboriginal Australians were granted the right to vote, and only in 1967 that the census recognised them.

Even today, despite some headway made by the 2008 government apology over the ‘stolen generation’ of Aboriginal children forcibly removed from their families between 1909 and 1969, ignorance and discrimination continues.

Aboriginal people are still denied the federal constitutional recognition they deserve as the country’s first people; although Prime Minister Julia Gillard did pledge a referendum on the subject in September 2010.

Professor Norris says he hopes his research could bring cultures closer together.

“It’s about the sky, which everyone understands.”