Science and sound come together to create a post-human music machine with real-world implications for brain training and therapy.

If the future is now, then Guy Ben-Ary is its musical conductor.

The US-born, Australia-based artist and researcher has created the world’s first neural synthesiser, ‘cellF’: a bio-engineered brain in a petri dish that can jam with real life human musicians.

cellF — pronounced ‘self’ — is what Ben-Ary calls a “wet analogue” instrument. It has a network of brain cells, or neurons, at one end, which grow on a specialised interface that allows two-way communication with a real life human musician at the other end. In between the two is a custom-built analogue synthesiser. Sounds from the live musician are captured by the synthesiser, and fed to the neurons as stimulation. The neurons respond by controlling the analogue synthesiser to output sounds to the human musician. And thus a cybernetic jam session ensues.

It is part sculpture, part instrument, part biological laboratory, and a collaborative effort involving a small team of scientists, engineers, and artists. But, at its heart — or, brain — it’s all Ben-Ary. He said he was inspired to create cellF by a “narcissistic desire to re-embody myself”.

“My long-standing passion for music, combined with 16 years of scientific research exploring artistic embodiments of bio-engineered ‘brains’, laid the foundation for creating this cybernetic self-portrait.”

It began with a biopsy. Ben-Ary had a sample of skin cells taken from his arm, which, using a technique called ‘Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell technology’, were transformed into stem cells. The stem cells were then “pushed down the neuronal lineage until they became neural stem cells, which were then fully differentiated into neural networks over a Multi-Electrode Array dish”.

That is to say, the stem cells were cultivated in a petri dish lined with electrical conductors, which act like synapses, to transmit and take in messages. Ben-Ary refers to it as his “external brain”.

A human brain contains approximately 100 billion neurons. The petri dish contains a symbolic brain composed of only around 100,000 cells. However, just like the real thing, it can produce a tremendous amount of data, respond to stimuli, and is subject to a lifespan.

Ben-Ary’s ‘external brain’ is housed inside a biological lab containing a high-precision tissue culture incubator, inside a biological safety cabinet for human genetically-modified material, inside a metal, gramophone horn-esque structure, that is the external facade of cellF.

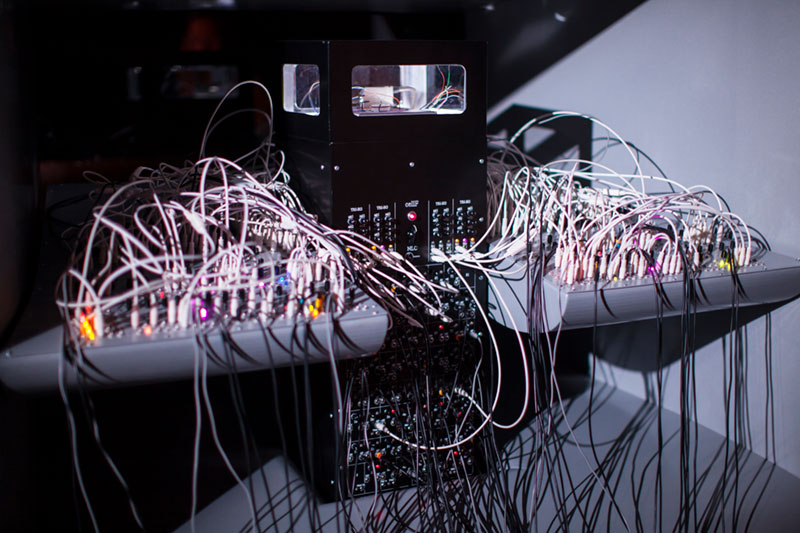

From the mouth of the horn — which is aesthetically influenced by the noise machines of Italian futurist Luigi Russolo — spews a tangle of cables that connect the bio-lab to the synthesiser. Both devices sit on a shelf across the centre of the mouthpiece, which has been dubbed by the horn’s designer, Nathan Thompson, as “the station of genesis”.

cellF can also connect to up to 16 speakers which, during live performances, are placed around the room to “spatialise”, or distribute, individual sounds based on which part of the ‘brain’ they were generated from. Ben-Ary says it “invites the audience to walk around the space as if they were walking around inside my external brain”.

It might look technical — and indeed it is a feat of scientific and musical engineering that took four years to realise — but Ben-Ary is quick to point out that “there is no programming, no computers, no zeros or ones; just biological matter and analogue circuits”.

cellF made its live debut in a performance alongside drummer Darren Moore in the Western Australian capital, Perth, in October 2015. The sound of the drums was fed as electric stimulations into cellF’s neural network, and cellF responded by controlling the synthesisers in an “improvised post-human sound piece”.

“During the performance there was a clear sense of communication and responsiveness between the human and the non-human musician,” Ben-Ary says, “together they performed a reflexive, improvised, jam session.”

It has since performed twice more — in June 2016 at an exhibition in Sydney, and January 2017 at a festival in Hobart, Australia. The plan is to collaborate with more musicians and musical ensembles to see how different musical styles might influence cellF’s functionality or ability to play.

“In the human brain music is known to entrain neural activity, and early music training in children alters brain structure and function. As a therapy in adults, music also enhances activity in brain circuitries after stroke or in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s.”

Ben-Ary says he hopes cellF’s “symbolic brain (will) entice the viewer to consider future possibilities that these technologies can present”.