“You wouldn’t believe how many goths we get posing outside for pictures,” says Father Brian Ralph, vicar of the church of St Barnabas at Bethnal Green.

At street level on the corner of Roman Road and Grove Road in East London, it’s not immediately obvious why. But as you gaze up the yellow and red brick tower, the answer comes in to view. A question, however, remains: why does a church have a pentagram on it?

“I just don’t know. Nobody does,” says Father Ralph, “We’ve asked a lot of people, and looked back in the archives, and we just can’t find anything.”

St Barnabas at Bethnal Green

The building was constructed in 1865 for the congregation of Revered Allan Curr and named the Union Baptist Church. It was designed by architect William Wigginton in the Gothic style “of the flowing middle pointed period” (according to a newspaper report of the time). But within a year of its completion Revered Curr moved on. Then, after influential Baptist preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon said the church was more “mass house” than Baptist chapel, it was sold to the Church of England and consecrated as St Barnabas in 1870.

Neither the London Baptist Property Board nor the Church of England Record Centre holds Wigginton’s original plans or any details of the pentagram’s significance. Tower Hamlets Library and Archives has nothing from Wigginton either. But its collection does include plans for the restoration work carried out on the church following World War Two. These drawings at least confirm the pentagram was part of Wigginton’s 19th century design. However, a spokesperson at the London Baptists Association said “we are not aware of any connection between five-pointed stars and Baptist churches”.

The pentagram is an ancient symbol that has variously been associated with the heavens, the human body, wisdom and mysticism. It is only relatively recently that it’s been linked with witchcraft and the dark arts, as we most popularly know it today.

Father Ralph says: “The only things we can think of is that it might be some kind of Mason’s mark or it’s just meant to be the Seal of Solomon.”

While he’s “not convinced” of the Masonic connection, there is some credence to the suggestion. The five-pointed star, although not referred to in Masonic rituals, is a symbol used on the regalia and jewels of office of leaders in the craft.

The Freemason and Masonic Illustrated number 58, published in 1890, confirms that Wigginton was a member of the organisation, but would a Mason be so blatant and bold with his symbology?

A source at the Freemasons says: “I have seen Masonic symbolism such as pentagrams in churches, but it is normally far more discreet – perhaps a small symbol in a stained glass window.”

St Barnabas at Bethnal Green

The Seal of Solomon is said to be the inscription on a ring belonging to the ancient king of Israel and son of David. Rabbi Professor Marc Saperstein, of Leo Baeck College, believes this was originally depicted as a pentagram. But, he says, around the 19th century the five-pointed seal was replaced by the six-pointed Star of David as a Jewish symbol.

If we are to believe that Wigginton’s designs were motivated by a soft spot for Solomon, the dates of his buildings could correspond to the changes in depiction of the Jewish star.

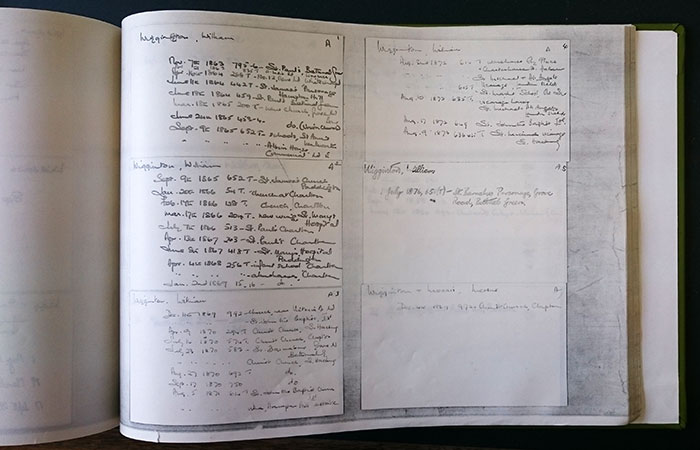

A facsimile of RIBA index cards listing William Wigginton’s building designs

Wigginton was a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects and most active between 1855 and 1873. He has more than 20 buildings to his name, the majority of which were churches and parsonages. However, most of these were destroyed during the Second World War, or subsequently demolished as a result of bomb damage. From the three churches still standing, and through examination of historic images of six others, a chronological pattern can be found:

St James’ in Hampton Hill (built in 1864), All Saints in Leyton, (1864), and St Barnabas (1865) each feature a five-pointed star.

St Paul’s in Charlton (1867), Christ Church in Clapton (1871) and Christ Church in South Hackney (1871) each feature a six-pointed star.

The William Wigginton-designed All Saints Church in Leyton, pictured c1905

More than 120 years on from his death, it is unlikely there can be a definitive answer on the presence of the pentagram in Wigginton’s work. But Peter Maxwell-Stuart, honorary reader in occult sciences at St Andrews University, offers a third theory. Dismissing any links to Freemasonry or Solomon’s Seal, he says:

“The pentagram is a very old symbol, and can be found in some of the art of the ancient world, and that of the early Middle Ages in Europe, as a decorative motif. Writers in the twelfth century started to merge the symbol with other notions, for example, the importance of the number five in relation to the human body, such as the five senses, and the idea that the human body symbolically reflected the greater world of the Creation, the macrocosmos.”

“So therefore, the pentagram was either a purely decorative symbol derived from the representation of a star, or an entirely Christian symbol representing the relationship of humanity with the divine world. Hence, I am not altogether surprised to find it on a church.”