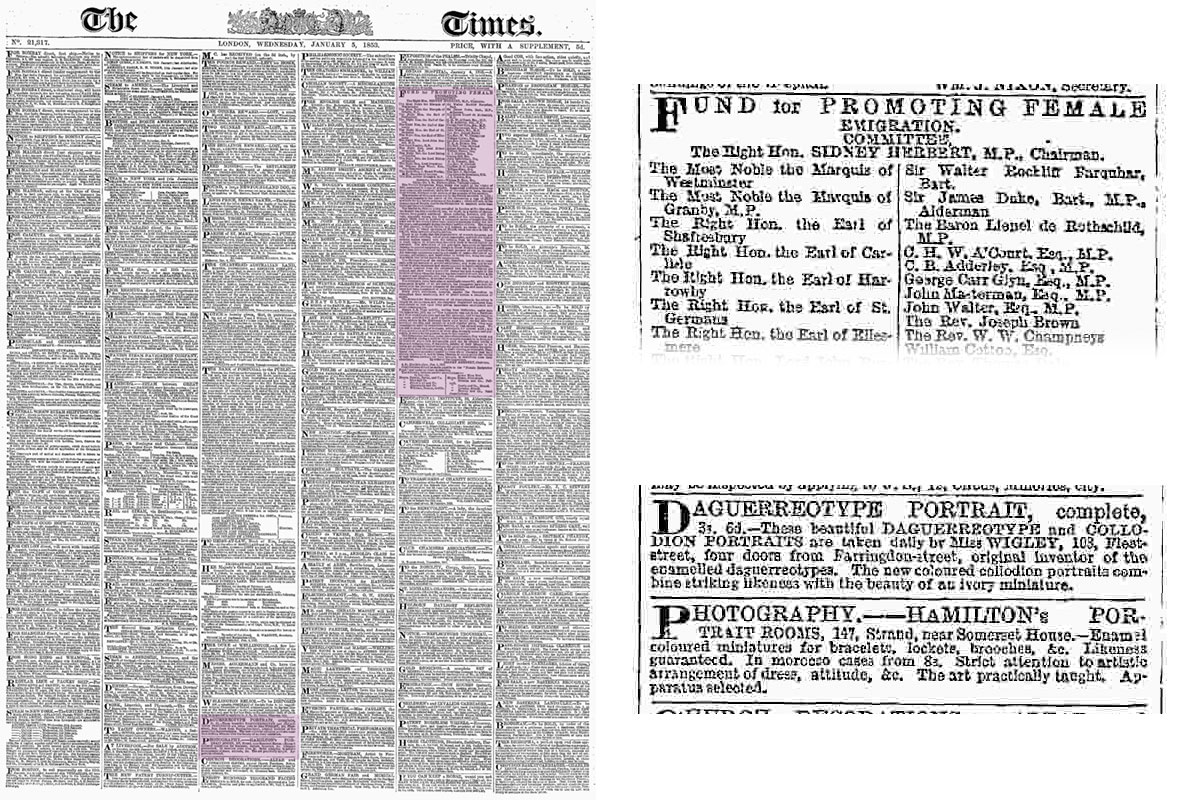

On the front page of London’s The Times newspaper on 5 January 1853, almost half the height of one column was dedicated to raising money for the Fund for Promoting Female Emigration to Australia. Elsewhere on the page were two small advertisements for women photographers: a Miss Wigley and a studio called Hamilton’s Portrait Rooms operated by a Miss Hamilton.

Dr Rose Teanby describes this juxtaposition as a perfect encapsulation of the possibilities that the emerging profession of photography offered women in this period.

“Photography could save single women from the prospect of emigration to become wives and mothers, and the possibility of never seeing their family again. Photography gave them liberation, the ability to stand on their own two feet, and be a productive member of society. It helped women along, and helped to show what women were capable of doing if they were given a chance.”

The front page of The Times newspaper from 5 January 1853, with highlighted and enlarged article about the ‘Fund for Promoting Female Emigration’ and adverts for two women photographers. Image courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive.

Last year Dr Teanby completed a PhD exploring the role of women in the first 22 years of photography in Great Britain and Ireland, from 1839 to 1861. To do so, she had to overcome the challenges of archives and official records in which women were obscured and previous studies in which women rarely appeared.

“People tend to repeat and build on what others have done. So, if women haven’t been reported by the people who wrote the original foundational texts of photo history, they’re going to think they mustn’t have been there. I started from the basis of questioning that. Instead of assuming that women weren’t there because the main authors have said as much, I worked on the basis that they were there, but they weren’t documented very well,” Dr Teanby explained.

Once she discovered her assumption was correct, Dr Teanby said her intention became “just to say: hey, look at all these women, aren’t they wonderful, and isn’t it terrible they’ve been forgotten”, but it soon evolved into “an amazing kind of revelation” about how photography gave many women independence.

A whole plate folding daguerreotype camera from 1840. Image courtesy of the Science Museum Group (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

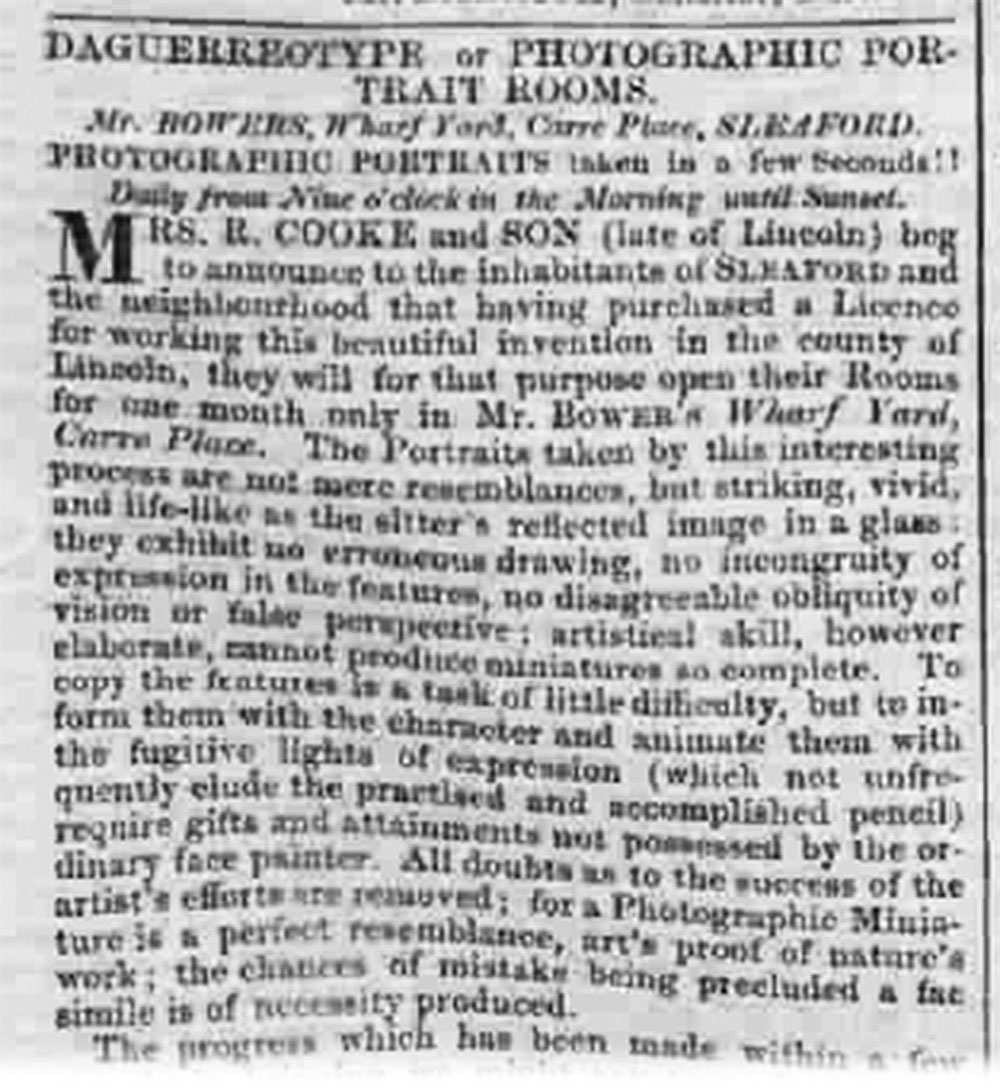

On 19 August 1839, Louis Daguerre formally announced a new photographic process: the daguerreotype. It used chemicals to produce a highly detailed image on a polished metal plate that had been treated with light-sensitive materials. In Great Britain and Ireland (unlike in France and other countries), a licence was required to practise daguerreotype photography professionally. But just five years after Daguerre’s announcement, Mrs Ann Cooke, a recently widowed mother of seven, became the first professional woman photographer in England. In the 1851 census she was the only woman recorded in England and Wales under that profession. It was a business she ran for over a decade.

When the daguerreotype patent expired after 14 years, “there was a big influx of women, in particular”, Dr Teanby says, because “there was no financial barrier now”. In the 1861 census, she found 168 women defined as photographers or photographic assistants.

Ann Cooke’s advert from The Lincolnshire Chronicle, 13 September 1844. It reads in part: ‘The portraits taken by this interesting process are not mere resemblances, but striking, vivid, and life-like […] artistical skill, however elaborate, cannot produce a miniature so complete.’ Image courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive.

“It was a brand-new invention – that’s one of the most interesting things about this period – everybody was kind of trying to find their feet. There wasn’t any inbuilt tradition of discrimination. I’ve been constantly surprised at how liberal the whole thing was.”

When the Royal Photographic Society was founded in 1853, its constitution explicitly stated that women were eligible for membership. And, as Dr Teanby explains, it was “very easy” to learn the skills required to become a commercial photographer.

“Several professional photographers who had already set up in a studio advertised tuition to anybody, man or woman, for a guinea a lesson, providing equipment afterwards. It was accessible, you didn’t need an apprenticeship, you didn’t need a degree, you weren’t excluded at the point of entry.

“When things were at their peak of suppression for women – no formal education, no vote, legal anonymity as soon as you get married – photography just cut through all that.”

In fact, Dr Teanby found evidence of the women’s rights movement supporting the development, and investing in the businesses, of women photographers, because the field was an exemplar of the equality they were advocating for and showed that women’s autonomy and self-sufficiency was possible. “It was quite a revelation, but it didn’t feature in the photographic history books I read,” she says.

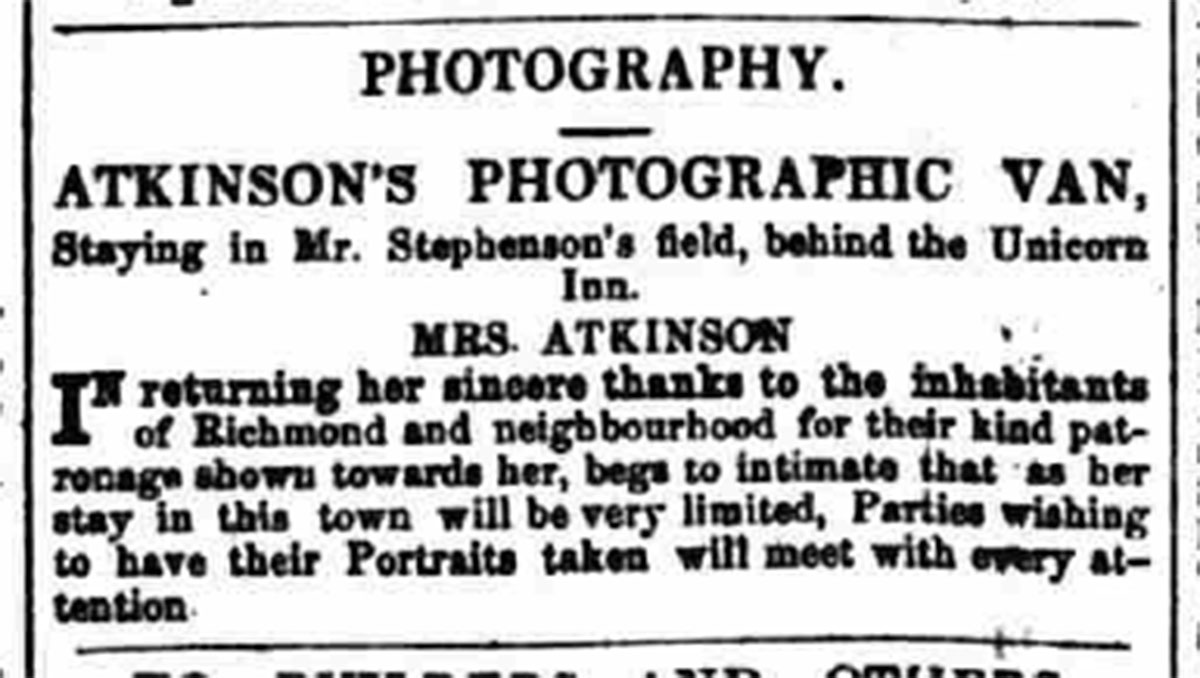

The British Newspaper Archive turned out to be one of the most valuable resources in Dr Teanby’s work. One of her favourite examples is the discovery of a travelling, or “itinerant”, photographer called Mrs Atkinson. All that is currently known about her comes from 1860s adverts in regional newspapers.

“We don’t know what her history is and what she did afterwards, that just isn’t traceable. She’s not in the census because she’s travelling all the time, so these little snippets of advertisements are massively significant. They tell you more than any official document. They show you she’s there, she’s travelling on her own, she’s providing a photographic service.

“And because she’s going to remote places – these people invariably wouldn’t have seen a photographer before – a woman then becomes the epitome of what photography is. This amazing new invention becomes synonymous with a woman.”

One of Mrs Atkinson’s adverts, from the Richmond and Ripon Chronicle, 24 March 1860. Image courtesy of the British Newspaper Archive.

Sadly, the most important evidence and record of the work of early women commercial photographers – the pictures they took – are almost entirely non-existent, or unidentifiable, today. (This contrasts with the record of ‘amateur’ photographers, such as Julia Margaret Cameron or Anna Atkins, who were better able to create and control their own archive.)

“That’s the really difficult bit. There are so few examples of women’s early commercial photography.

“They obviously had to be of a certain standard because people were paying them money, but otherwise their work is almost anonymous. Daguerreotypes were a one-off image, so they’d hand it to the person who’s giving them the money, it goes on that person’s mantelpiece, and it’s passed down a couple of generations. By the time it gets beyond that, the family might not even remember who the person in the picture is. There must be loads of them that have ended up in skips. It’s horrible to think about.”

Despite the challenges presented by the silences in the historic record, Dr Teanby is determined to raise awareness of the contribution of women commercial photographers in Britain during the field’s early years.

“There’s an element of women’s history where they’re only celebrated if they’re exceptional. But Ann Cooke, the lady who bought the first commercial photography licence, was just an ordinary woman who had to start her life all over again in her early 40s. It’s that quiet resilience, and quite gutsy approach to life, and just getting on with it, that doesn’t get noticed or celebrated very much. She’s not what you would usually call exceptional, but I would say that she is extraordinary. And it’s people like her that need to be shoehorned into accounts of history as much as possible.”