During my master’s degree studies, I took a module on archives and memory. One day we were discussing an article about the social history of the archive, and specifically, ‘recipe’ books as a historical source.

A member of the class asked a question along the lines of: ‘Why would anyone / any archive be interested in a woman’s recipe book?’. Internally I seethed at his lack of imagination and the sexist undertones (overtones?) of his comment, while externally – given what I thought was clear from the context of the article and the discussion – I couldn’t help blurting out: “The recipe book is the archive!”.

But let’s give the questioner the benefit of the doubt for a moment (perhaps he hadn’t actually read the article?).

The ‘recipe’ book (or ‘receipt’ book, to use the language of the era) we were talking about wasn’t simply a catalogue of instructions for cooking a nice meal. It was a multi-generational record of, yes, food recipes, but also practical medical knowledge and family history. And the large number of these books that survive to us today (often dating from the early modern period, spanning the 16th to 18th centuries) reveal they weren’t only written by women, either.

As Alexandra Walsham explained in the article we were discussing in class that day, as historic sources, recipe books can reveal fascinating insights into everything from family traditions and dynamics, to domestic lore and informal scientific practice, as well as literacy, record keeping, and life writing practices.

For their owners, these books were family heirlooms, in some cases considered valuable enough to be mentioned in wills. For historians and researchers, they provide a unique glimpse into the private sphere of the early modern household and challenge perceptions around knowledge production and transfer.

Writing on the subject of recipe books, Elaine Leong has said that “while early modern women were actively involved and played a significant role in the making of household knowledge, they were joined in these endeavours by their fathers, husbands, brothers and sons,” and suggests that “communities of knowledge-collectors rather than single authors were behind the making of these books”.

Rather than ‘recipe’ books, Leong says they are better described as “family treasuries of practical knowledge”. Each new keeper benefits from the efforts, the trying and testing, of the generation before, while taking on responsibility for adding to the collection for the next.

And the information these books contain is almost as varied as the ways in which they entered and were passed down through families.

Knowledge transfer

- In 1610, widower Valentyne Bourne began a book which, 26 years later, he bequeathed to his daughter, Elizabeth. Blank pages were left at the end of certain sections, suggesting his hope that she would continue to add to it. These types of books are known as ‘starter’ collections.

- When Mary Cholmeley married Henry Fairfax in 1627, she brought a recipe book with her into her new family. On the front and back covers it features the initials ‘MC’, which may be for Mary, or her mother, Margaret Cholmeley. The Cholmeley/Fairfax book was passed through the extended family for over a century before it was rediscovered in a chemist’s building in the 1880s.

- In the will of Lady Frances Catchmay, who died in 1629, she left instructions that her several books of ‘medicines, preserves and cookery’ should go to her son, William, “Earnestly desiringe and Chardginge him to lett every one of his Brothers and Sisters” have full or partial transcripts. She wished to pass her accumulated knowledge onto not only her eldest child, but all of them.

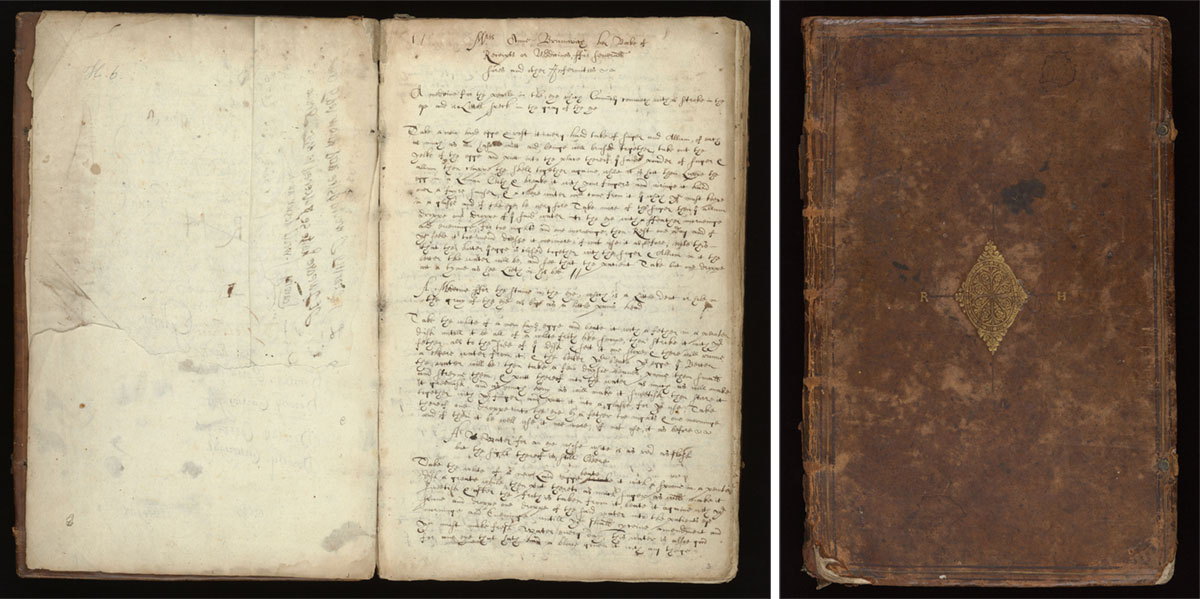

- When Rhoda Chapman Hussey married Ferdinando Fairfax in 1646, she brought the recipe book she’d used in the home with her first husband, Thomas Hussey. But, in fact, the Wellcome Collection describes this book as originally created by Anne Brumwich, who died 1628. (After the inside front page – where each new owner traditionally writes their name – Rhoda, or “Lady Hussey”, appears in the book for the first time on page 39 with a recipe for a canker in the mouth attributed to her.) The Brumwich/Hussey/Fairfax book passed through at least three generations of Rhoda’s female descendants (and includes a step-daughter’s name on the inside front pages, too) before it was sold as part of a library auction in the early 1900s by the family Rhoda’s great-granddaughter married into.

- Sir Peter Temple created a book “for my dear daughter”, Elianor, around 1656, which includes further recipes contributed into the 18th Century.

The Brumwich/Hussey/Fairfax book, in which the title page (left) says “Mris Anne Brumwich her Booke of Receipts or Medicines, ffor Severall sores and other Infermities”, while the cover (right) features the initials, “R H”, of Rhoda Chapman Hussey. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Knowledge production

- The Bourne recipe book, which is held in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, contains medical, veterinary, and culinary recipes, as well as weights and measures conversion charts, a glossary of medical terms, and extracts from the works of the ancient Greek physician, Galen. It also includes family history (the dates of births, deaths, and marriages) and local history (lists of Norwich mayors and sheriffs, and Norfolk high sheriffs).

- What survives of the Cholmeley/Fairfax book is a “reproduc[tion] in fac-simile of the handwritings” called ‘Arcana Fairfaxiana’, which is held at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. It was produced in 1890 and includes a printed introduction by George Weddell, who discovered the original book in the chemist’s building. The recipes are medical (“The Drinke for the Plage”, “For the swyming in y’ head; given by Mr Vesalius (ye Emperor Charles phisition) to Quene Mary”) and culinary (from making “Cramd Capons”, or stuffed cockerel, to pancakes and gingerbread), as well as covering household tasks such as bleaching, dying, brewing, and preserving. Weddell also describes “occasional appeals to the imagination, in the form of charms or talismans”. There is evidence that recipes were copied from professional sources, such as apothecaries’ books, and contributed by the extended family, including examples written in the hands of Mary’s brother, Henry Cholmeley, and Henry Fairfax’s brother, Ferdinando. Weddell additionally describes the book as “swelled” by numerous cousins and countless nieces.

- Only a single volume of the Catchmay books survives, held in the Wellcome Collection in London. It contains over 950 recipes – starting with “A prayer to be sayd at all tymes to defend thee from thy Enemyes” – that cover everything from dealing with aches, burns, coughs, and colds, to fever, gout, migraines, plague, and pestilence, as well as remedies to staunch bleeding, induce vomiting, and hasten a birth. Some of the recipes include the source, such as “Goodwife Wittmans water to washe corrupte or dangerous woundes withal” and “Mrs Clyffes medicen for the palsey”. Others include a note on effectiveness, such as “A medicen for wartes proved” and “A Reciept to make Sirropp of Roses the Best”. The book also includes remedies for animals, such as “for a beast that hath eaten a taynte worme” and “A medicen for a mangy horse or dogge”, plus a section at the end with 17 dedicated horse recipes across five pages.

- The Brumwich/Hussey/Fairfax book, which is held in the Welcome Collection, stands out to me for the detail of its recipe titles – their specificity, their breadth of purpose, and endorsements of their value or effectiveness. For example: “An aproved medison for all sorts of Agues: to be Layd on six houres before the fit come: & if posible: used before they have had six fits”, “An excellent Balsome curinge many disseases & all desperate wounds in the space of 24 hours”, and “A very rare Receipt of Mrs Huttons which cuered her of a cancer in her breast & for which 3 score pound had been given for the receipt”. They also provide intriguing peaks into broader social history, such as with “A Receipt to prevent miscarrying sent to my Sister Cartwright by her neece the Duchesse of Buckingham” and “An Excelent receipt for the plague wch did help 600 in York & in one house wher 8 were Infected 2 of thm drunk of it & lived the other would not & dyed”.

- The Temple book, which is held by the British Library, starts with medical recipes arranged in rough alphabetical order. This is followed by additional sections of themed recipes under the headings: “Cookery”, “Made wines”, “Perfumes”, “Husbandry” (for sowing crops, etc), “Horses” and “Dogs” (both for diseases), “Fishing’” (recipes for bait, etc), “Rabbits” (recipes for catching), and “Experiments”. Inserted at the end are “The true Receipts of that valuable secret for curing all sorts of Ruptures in men, women and children”, said to have been sold to the King by Thomas Renton. Throughout, the book includes notes on the origin of the recipes and the trustworthiness of their authors, and Temple endorsed particular entries with his initials, “PT”.

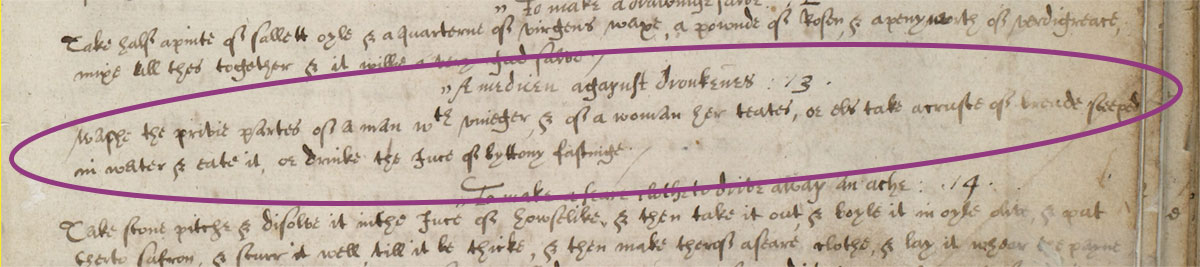

An amusing “medicen agaynst dronkenes” from Frances Catchmay’s recipe book. Method: “washe the pivie partes of a man with vineger, & of a woman her teates, or els take a cruste of breade steeped in water & eate it, or drinke the [j]uce of byttony fastinge.” Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Family archives

A little reading – of the literature and the books themselves – quickly shows that, despite what my classmate thought, early modern era recipe books were (to quote Leong) “not housewifery guides authored by individual women but household books filled to the brim with the collective knowledge of a family”.

She continues: “Husbands and wives, fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters all contributed to, wrote in and owned these books. Sons and daughters inherited the books and the practical knowledge contained within. As new owners sought to individualize and customize the books to their own and their family’s needs, they collected and added new recipes and tested and adapted old ones. The result was a book which lay at the heart of the household, a central place to record practical medical and culinary knowledge. When seen from this angle, it is not surprising that a number of compilers combined family history with recipes, for in some ways the recipe book was [as I blurted!] a kind of family archive.”

Sources:

- Bourne, Valentyne, ‘A Common-Place Book’, 17th Century | Bodleian Archives & Manuscripts.

- Brumwich, Anne (& Others), MS160, Recipe Book Collection: Wellcome Collection, FromThePage.

- Catchmay, Lady Frances (d.1629), MS.184a, Recipe Book Collection: Wellcome Collection, FromThePage.

- ‘Elianor Temple: Collection of recipes made for, by her father: 17th cent’, Stowe MS 1077, British Library Archives and Manuscripts.

- Leong, Elaine, ‘Collecting Knowledge for the Family: Recipes, Gender and Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern English Household’, Centaurus; International Magazine of the History of Science and Medicine, 55.2 (2013).

- Walsham, Alexandra, ‘The Social History of the Archive: Record-Keeping in Early Modern Europe’, Past & Present, 230, Supplement 11 (2016).

- Weddell, George and Fairfax family, ‘Arcana Fairfaxiana Manuscripta : A Manuscript Volume of Apothecaries’ Lore and Housewifery Nearly Three Centuries Old, Used, and Partly Written by the Fairfax Family’ (1890), Internet Archive.