Findings from an analysis of almost 27,000 history outputs from 2024. This is the second in a series of articles drawn from my Public Histories MA dissertation. (Read part one.)

~

In a 2016 interview with English Heritage, the historian, author, and broadcaster Dr Bettany Hughes said: “women have always been 50% of the population, but only occupy around 0.5% of recorded history. Clearly something has gone wrong here, the maths just doesn’t work.” It is a statement and a statistic that has been widely repeated – and questioned – in the years since. Hughes has not shared her working, so it could be argued that the figure is more of a rhetorical device to illustrate women’s under-representation than a quantitatively researched fact.

I can’t possibly look at the whole of recorded history, but what might an analysis of a snapshot of history outputs – academic and magazine articles, books, podcasts, and newsletters – published in 2024 tell us?

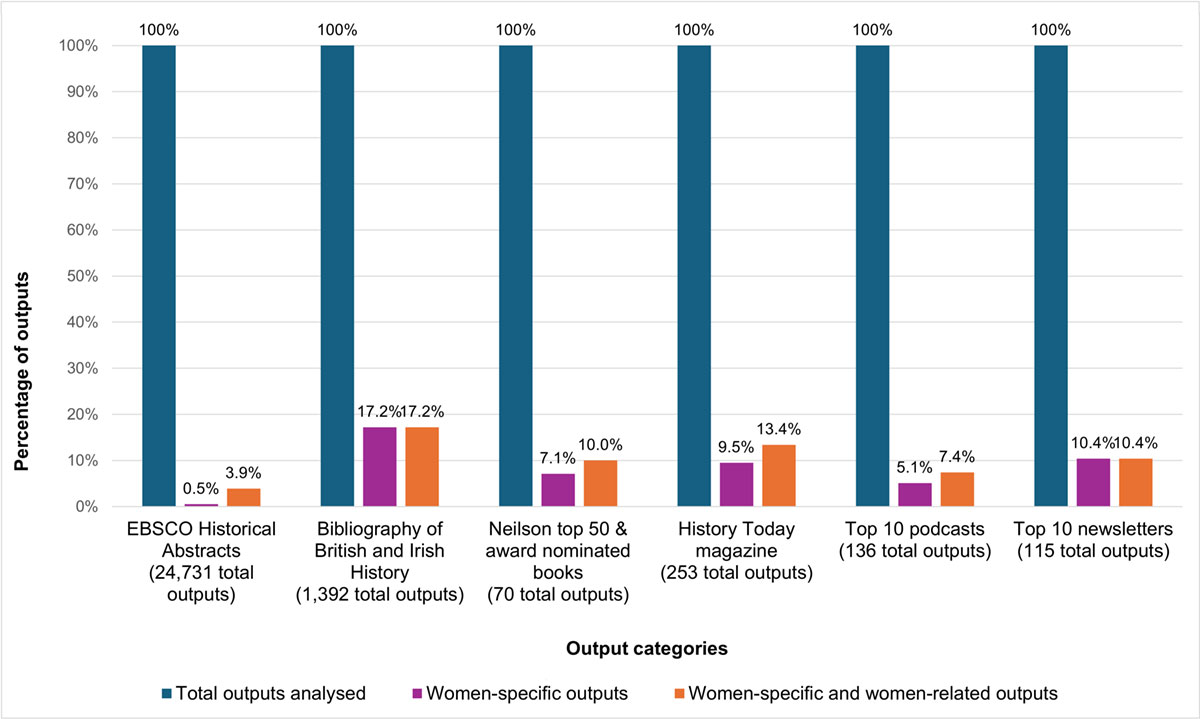

Focusing first on academic history outputs published in the last full calendar year, I searched Historical Abstracts via EBSCO, looking at all English language publication types from January-December 2024 inclusive. The search returned 24,731 results. When filtering using the category: women’s history, the number was just 125 (0.5% of the total published items). This matches Hughes’ figure.

But in order to compare multiple sources as accurately and as fairly as possible, allow for variations in the specificity of filters, and the subjectivity of human categorisation and tagging, I broadened the search terms to include women-related topics as well. Repeating the search, this time with added available relevant categories – feminism, women’s rights, widows, marriage, gender, and violence against women – the number of results increased to 963 (3.9% of the total).

The findings were more positive for women’s representation in the Bibliography of British and Irish History. A search of all publications for the year 2024, using no filters for subject, place, or century, returned 1,392 results. When filtering by subject: women (the only applicable filter), the number was 240 (17% of the total).

It is interesting to note that neither database provided an equivalent filter for men’s history or men (although Historical Abstracts did include some men-related themes – brothers: 189 results; fathers: 118 results; and masculinity: 107 results).

Across these two academic databases, women-specific topics made up 1.4% of the 2024 academic history outputs analysed, rising to 4.6% when taking into account both women-specific and women-related topics.

Expanding the analysis further to look at 2024 history outputs aimed at a wider, more general public audience – what might be considered popular history – the results were slightly more positive again.

Combining Nielsen BookScan data of the top 50 selling non-fiction history titles in the UK in 2024, with the books shortlisted for The Wolfson History Prize, and the longlist for the Historical Writers’ Association non-fiction Crown Award, provided a total of 70 books for analysis. Of those, just 5 (7.1%) focused on women-specific topics, rising to 7 (10%) when including also women-related topics.

History Today magazine, whose strapline is ‘The world’s leading serious history magazine’, published 253 articles across its 12 monthly issues in 2024. Of those, 24 (9.5%) dealt with women-specific topics, and a further 10 with women-related topics, taking the total of women-specific and women-related topics across the magazine’s output for 2024 to 34 (13.4%).

A representative random sample* of shows released in 2024 by the top 10 history-themed podcasts across Apple and Spotify (as at 31 December 2024) totalled 136 episodes. Of those, 7 (5.1%) discussed women-specific topics, rising to 10 (7.4%) when including also women-related topics.

A representative random sample* of posts published in 2024 by the top 10 history-themed newsletters on Substack (as at 31 December 2024) totalled 115 stories. Of those, 12 (10.4%) dealt with women-specific topics. None of the newsletter posts sampled wrote about broader women-related topics.

*The representative random sample was based on 10% of, or 10 episodes/posts, whichever was the higher figure. This approach was chosen to provide greater consistency across the top 10 podcasts and newsletters, whose individual show/post numbers varied considerably.

Across these four formats of public-focused history outputs analysed, women-specific subjects made up 8.4% of the 2024 outputs, rising to 11% when taking both women-specific and women-related topics into account.

The combined total of all the data analysed for this snapshot of history outputs published in 2024 was 26,697 articles, books, podcasts, and newsletters. Of those, just 413 (1.5%) were focused on women-specific topics, rising to 1,266 (4.7%) when considering women-specific and women-related themes. While these figures were higher than the one quoted from Hughes (albeit marginally, in the women-specific instance), they nonetheless demonstrate a significant under-representation of the presence and contributions of women in the past in history outputs.

This is what the data looks like:

A chart showing the percentage of women-specific, and women-specific and women-related, outputs published in 2024 across six history output categories, as described in the paragraphs above.

It is a disappointing and dishearteningly unequal state of play; one which feels closer to the conditions that inspired the establishment of women’s history as an academic field in the 1960s, rather than that of a genre of history with over 50 years of dedicated work behind it.

There are challenges further up the pipeline, too.

I’ve mentioned in a previous post the research from End Sexism in Schools that found women were significantly under-represented in UK secondary school history lessons. One of my fellow history MA students gathered some of the data for that report. Laura Aitken-Burt analysed characters listed in history GCSE and A-level specifications (for students typically aged between 14 and 18) across the three United Kingdom exam boards. She also sampled 28 textbooks published between 2010 and 2022 that were currently in use in classrooms to understand how those specifications were being interpreted and what level of women’s representation they supported. The results were “stark”: of the 1,998 named characters, 1,863 (93%) of them were men, and just 135 (7%) were women. Furthermore, 67% of history A level and GCSE specifications did not include a single woman character to study. Women were, Aitken-Burt said, “all but invisible throughout every specification and textbook” and that even “quadrupling the current numbers would be nowhere near an equitable 50% coverage”. How can we move the needle when the history practitioners of tomorrow are not being taught a balanced understanding of the past and women’s contributions to it?

And (higher eduation crisis aside for the moment) how will the rise in the use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) impact the rigour inherent in the practice of history, the research and critical thinking skills required? And trained as they are on sources which my research has proved are not representative, are we at risk of AI tools creating a series of new history outputs that cyclically feed on each other, eventually writing women and other minoritised identities out of history all together? For example, studies of AI tools have found they amplify stereotypes associated with women more than those associated with men.

It feels bleak, but there are reasons to be optimistic. As I’ll explore in next fortnight’s post, there are plenty of people committed to the battle for fair representation of women’s presence and contributions in the past.

In the third post in this series, I’ll examine how women’s under-representation in history outputs influences women history practitioners.