In the 1650s in Salisbury, southern England, 80-year-old Anne Bodenham was hanged for witchcraft. She was a cunning woman, or occultist, who had learned her craft by reading books from the library of astrologer and practitioner of the ‘magical arts’, Dr John Lambe. Alongside feats of divination and shapeshifting, Bodenham also recited passages from books to raise spirits and wrote charms at the request of her customers. It was remarked upon that she sometimes wore spectacles.

At the same time and place, Anne Styles was working as a maid when she approached Bodenham seeking a spell to save her mistress from a poisoning plot. (This was not the first time Styles had visited, or paid for the services of, the cunning woman.) Bodenham wrote a charm for the mistress. She also persuaded Styles to sign her name in blood in a special red book, as a contract with the devil. Styles couldn’t write, so Bodenham guided the pen for her.

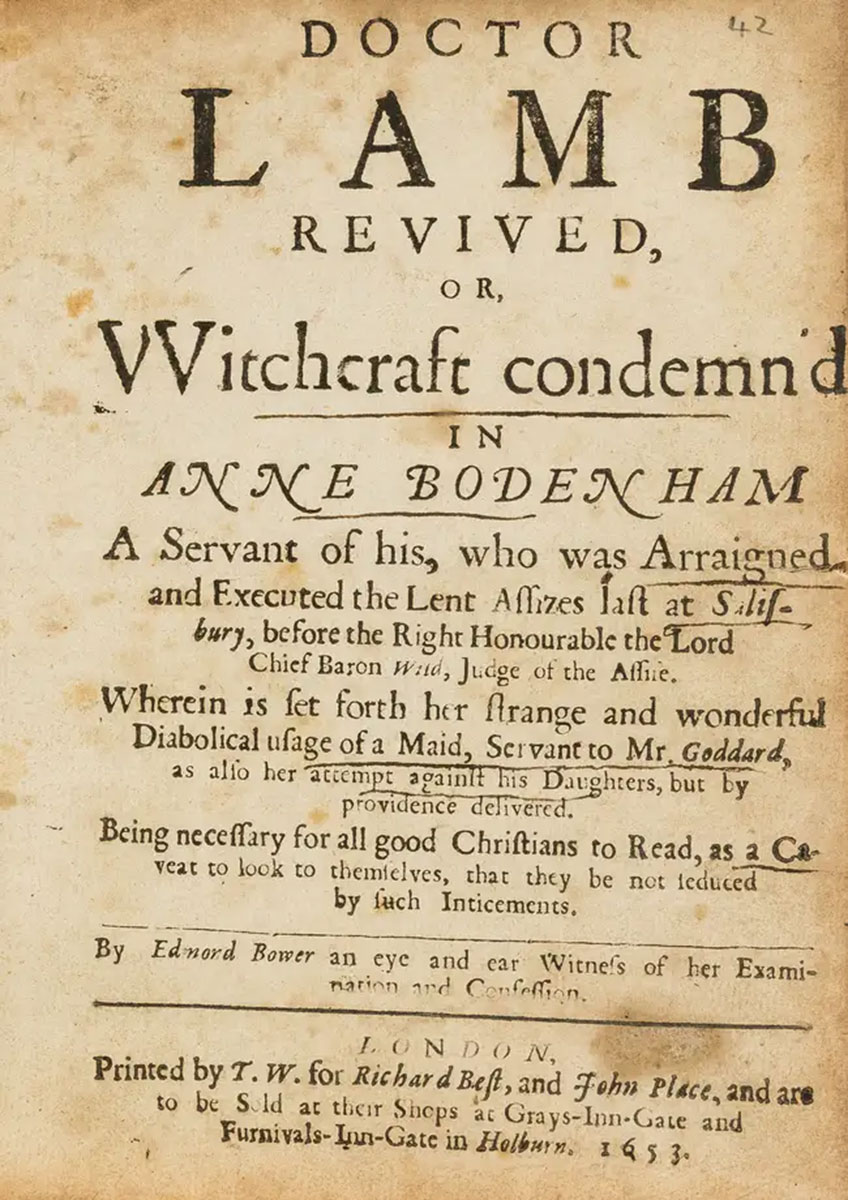

In a 1653 pamphlet detailing the case of Bodenham and Styles, ‘Doctor Lamb [sic] Revived, or, Witchcraft Condemn’d in Anne Bodenham a Servant of His’, Edmond Bower linked Bodenham’s witchcraft and criminality to her literacy, while at the same time linking Style’s illiteracy with vulnerability to the temptation of witchcraft and the devil.

As Frances E Dolan wrote about this case in ‘Reading, writing, and other crimes’: “witchcraft could be associated with either ‘illiteratenesse and want or learning’ or ‘the reading and study of dangerous books’ […] Thus, either literacy or illiteracy can lead women to witchcraft.”

An original copy of Bower’s pamphlet sold in 2021 for £950. Image courtesy of Forum Auctions.

About 60,000 people were executed for the crime of witchcraft in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the British Isles there were around 5,000 witchcraft trials, more than half of which were in Scotland (and of those in Scotland, it’s estimated at least 54% resulted in execution). At least 75% of the people accused of witchcraft in England and Scotland were women.

In his analysis of demonological texts, Stuart Clarke found that women were overwhelmingly associated with witchcraft, based on the cliches of the period. Indeed, Alison Rowlands has said: “we must accept the fact that the patriarchal organisation of early modern society was […] a necessary precondition for witch-hunts that produced predominantly female victims”. Likewise, Christina Larner has concluded that “witchcraft was not sex-specific but it was sex-related” and that “the women who were accused were those who challenged the patriarchal view of the ideal woman”.

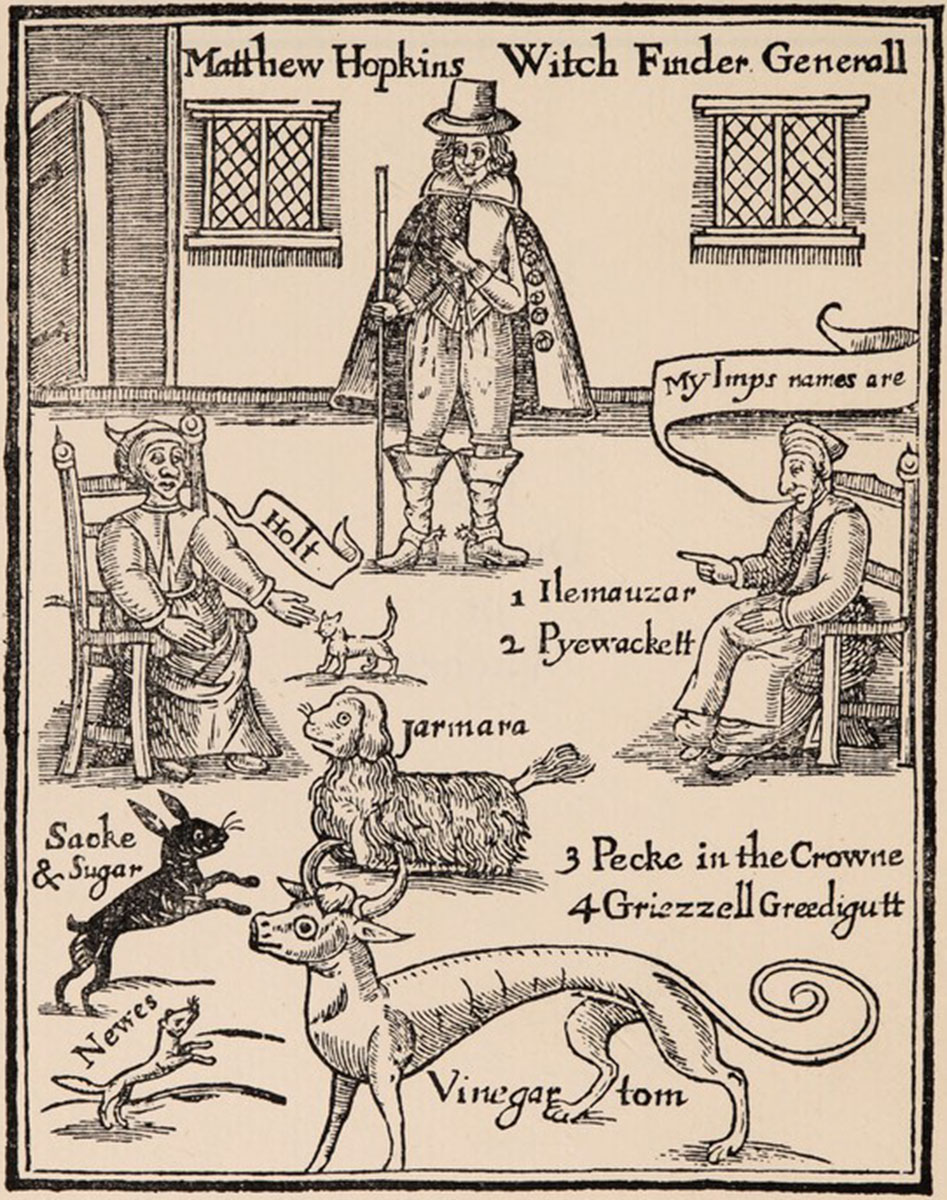

Interestingly, in Keith Thompson’s ‘Religion and The Decline of Magic’, he said that it wasn’t until the 1640s, and the investigations of the self-proclaimed ‘Witchfinder General’ Matthew Hopkins, that records emerge of people testifying to written pacts with the devil.

Frontispiece from Matthew Hopkins’ 1647 ‘The discovery of witches’. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.]

And so, back to the specifics of literacy and witchcraft, and the two Annes of 17th Century Salisbury.

In Bower’s pamphlet, he recounted Anne Bodenham’s description of how she did (under Dr Lambe) – and others could – learn witchcraft: “If those that have a desire to it, doe read in books, and when they come to read further then they can understand, then the Devil will appear to them, and shew them what they would know; and they doing what he would have them, they may learn to doe what they desired to do, and he would teach them.”

Reading being such a significant part of her criminality, Bower tried to use Bodenham’s library against her at her trial. He was particularly interested in “that Book that did raise the Spirits” and the one Styles had signed in blood, which he was sure would include other “names of Witches that had listed themselves under the Devils command”. But the only books Bodenham would allow him to have “were nothing concerning her art”. He concluded the first part of his pamphlet by describing Bodenham’s life as “wicked” and her death as “wofull”.

Meanwhile, the pamphlet continued, after spending several weeks in prison, Anne Styles was allowed to “go away home” and hoped to “begin a holy life”. Part of her plan to earn God’s mercy, to redeem herself for having previously “given my soul to the Devil”, was to overcome her illiteracy!

“I am not yet too old to learn, I will learn to read, sure, if God will be pleased that I shall.”

Um, does anyone else spot the flaw in the logic here? The skill that led one woman to witchcraft was acceptable as part of the redemption from witchcraft of another?!

As Dolan said: “In relation to literacy, most early modern women could not win.”

Sources:

- Bower, Edmund, Doctor Lamb Revived, or, Witchcraft Condemn’d in Anne Bodenham a Servant of His, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections (1653)

- Clark, Stuart, Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe (1999)

- Dolan, Frances E., ‘Reading, writing, and other crimes’, in Feminist Readings of Early Modern Culture: Emerging Subjects (1996)

- Larner, Christina, Enemies of God: The Witch-Hunt in Scotland (1981)

- Lee, Sidney, ‘Lambe, John (d.1628), Astrologer’, Dictionary of National Biography 1885-1900, via Wikisource

- Levack, Brian P., The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (1995)

- Rowlands, Alison, ‘Witchcraft and Gender in Early Modern Europe’, in The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America (2014)

- Thomas, Keith, Religion and the Decline of Magic (1971)