In last fortnight’s post about women’s role in the development of commercial photography in Great Britain and Ireland in the mid-19th Century, I mentioned that the Royal Photographic Society allowed women membership from its inception in 1853.

What I didn’t explicitly say was how unique that was. Almost 50 years on, at the turn of the 20th Century, many other of the major learned societies still excluded women – including the Royal Society, the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Astronomical Society, the Geological Society, and the Linnean Society.

Since 1900, botanist Marian Farquharson (born Marian Ridley in 1846) had been campaigning for better rights and representation for women naturalists at the Linnean Society of London.

Spoiler: she was eventually successful, and then she was ‘blackballed’ for it.

The original carte de visite photograph of Marian Farquharson submitted alongside her application for fellowship of the Linnean Society of London. Image courtesy of the Linnean Society.

Marian married ‘gentleman agriculturalist’ Robert Francis Ogilvie Farquharson in 1883, but had been an active field botanist for at least several years before this. In 1881 she was elected a member of the Essex Field Club and presented its library with an album of 38 herbarium sheets of British ferns. The same year she published the 100-page book, ‘A Pocket Guide to British Ferns’. From 1885, she began writing and presenting papers on mosses and ferns at smaller field clubs and naturalist societies. And by the end of the century, Farquharson – now a widow – was advocating for ‘Work for Women in the Biological Sciences’ via a paper read on her behalf at the 1899 International Congress of Women held in London.

In an article for a special edition of The Linnean journal, Peter G Ayres describes how the Congress was a sign that “women were becoming more organised, and less patient with their position in scientific society”, adding that women had been “effect[ing] minor breaches” at the Linnean Society since 1887, such as having their papers read by men at meetings and being invited by men as guests to meetings.

Farquharson petitioned both the Linnean and Royal societies in April 1900 asking that suitably qualified women be eligible for fellowship. Ayres describes the move as a product of the time, but that it also showed Farquharson “taking the lead, prepared to be the focus of male dissention”.

The Royal Society rejected the petition. The Linnean Society said it had been incorrectly submitted. She re-submitted to the Linnean, twice, but it took until the beginning of 1903 for the Linnean Society to agree to amend its charter to allow women fellows, another 15 months to write the amendment, and a further seven months for the amendment to be approved.

Two weeks later, on 17 November 1904, 16 names were put forward as the first potential women fellows of the Linnean Society of London. Fifteen were accepted. Only Marian Farquharson was rejected.

Ayres’ article considers whether the cause of Farquharson’s exclusion was that “her scientific credentials [were] not sufficient, or was she personally objectionable?”.

Given it’s been described that the credentials of several of the other women accepted for fellowship was their relationship – wife or daughter – to existing Society members, it’s hard to accept it was the former. (I intend no shade to those women, and in fact, I acknowledge that such simplistic descriptions are unlikely to represent the full story.)

What’s more likely is that Farquharson was, as Ayers suggests, considered too “forthright in her views”, too “proud and haughty”. In other words, she was guilty of daring to challenge the male status quo, and succeeding. In an article on its website, the Linnean Society describes the treatment of Marian Farquharson as ‘shameful’.

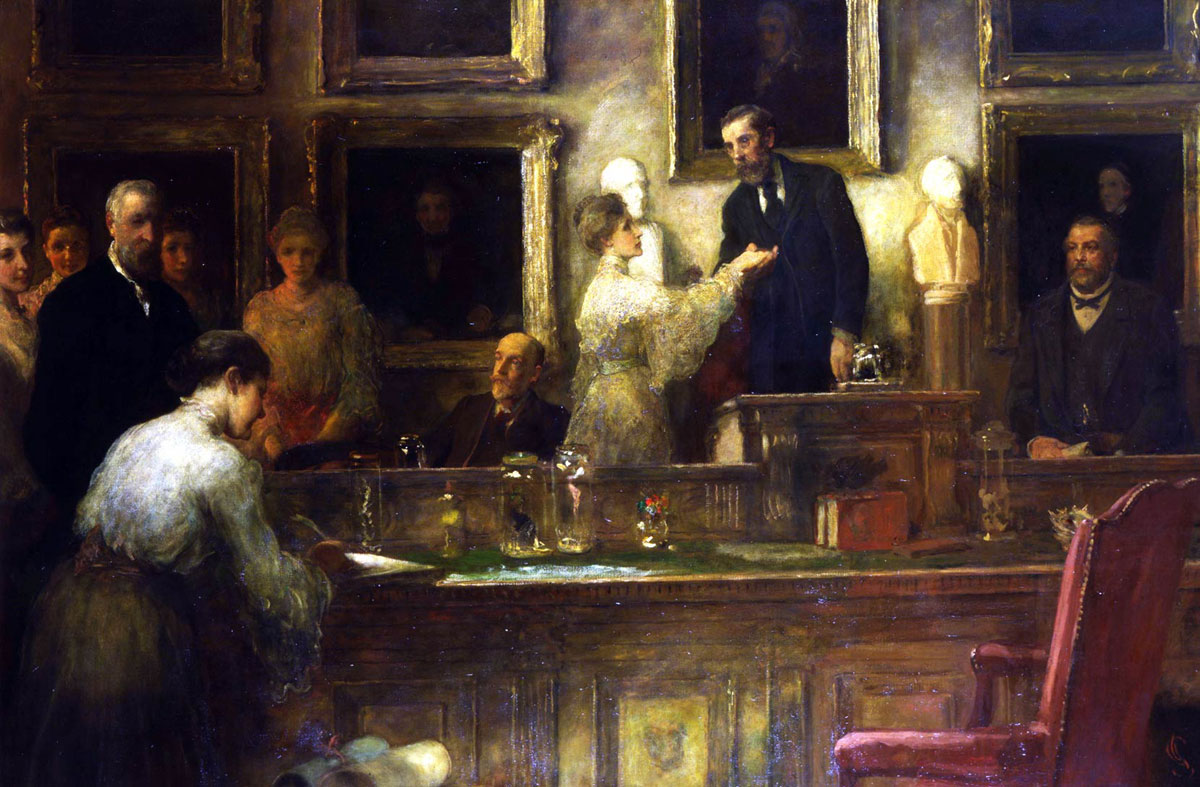

‘Linnean Society of London: First Formal Admission of Women Fellows’ by James Sant, 1906. The painting is on display at the Linnean Society of London.

It was another four years before Farquharson was eventually approved for fellowship, but sadly, her ill health – which had been what inspired her to begin exploring nature decades earlier – prevented her from ever attending the meeting at which she’d be formally admitted.

She died in 1912, never able to officially enjoy for herself the rights she’d fought to win for all women naturalists.

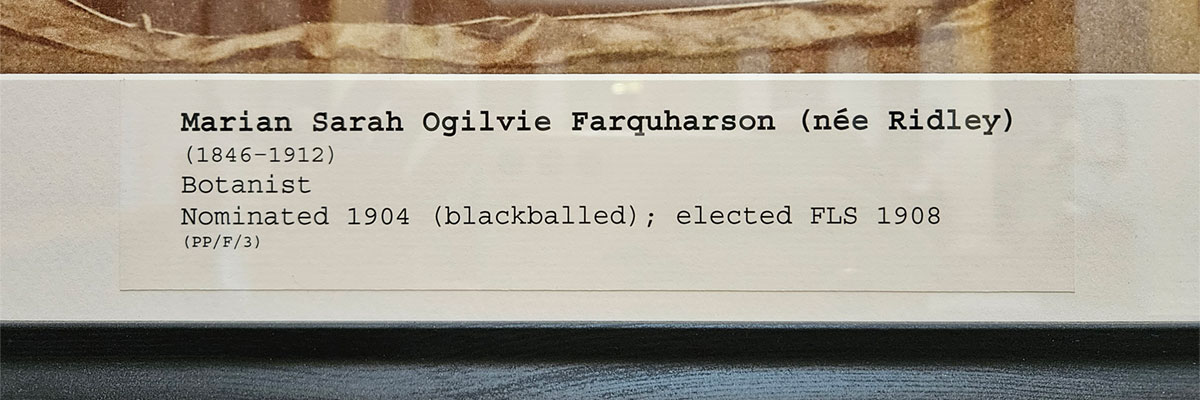

The portrait of Marian Farquharson currently on display in the library of the Linnean Society of London, with a close-up of the label describing that she was ‘blackballed’ from fellowship in 1904.