Full disclosure: I am not impartial to the challenge posed in this story. I am the type of person I am addressing the above question to. But as a historian, I know the evidence says the answer must be ‘yes’.

My rethink was sparked by a recent article by Rita Voltmer which – in the simplest terms – calls out scholar/author/teacher/activist Silvia Federici for continuing to perpetuate myths about the European witch hunts of the 16th and 17th centuries.

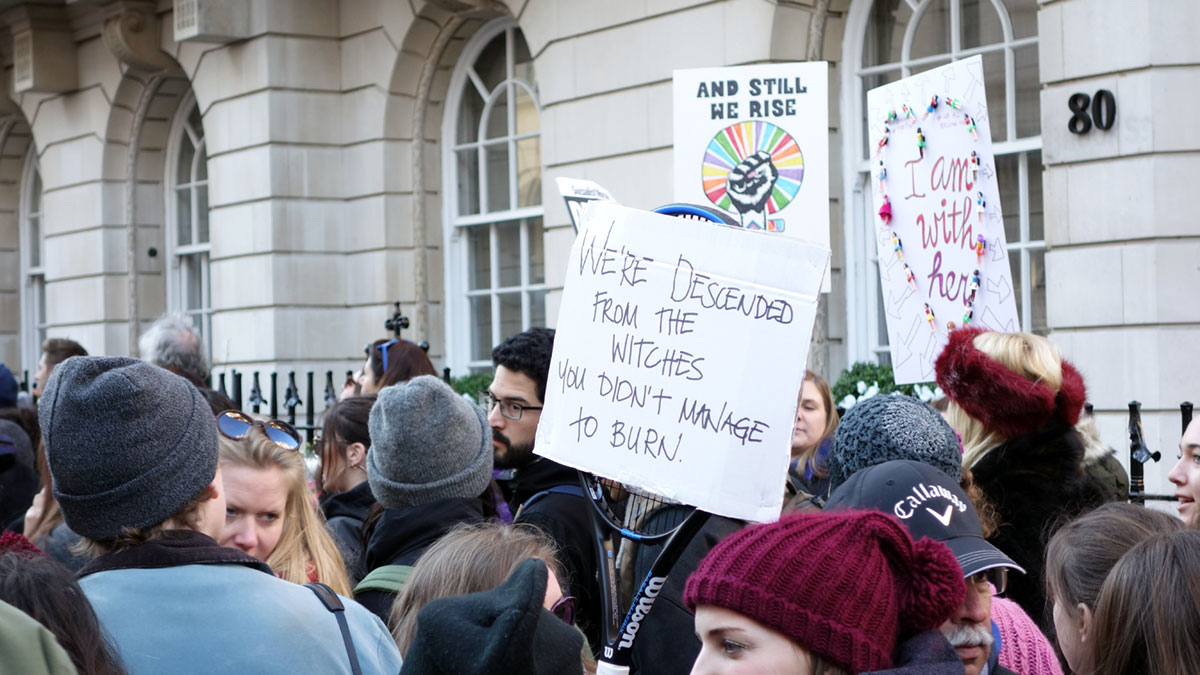

I’m not going to lie, I love this painting by John William Waterhouse, which depicts some of the myths we’ll cover below. ‘The Magic Circle’ (slightly cropped), 1886.

Federici is the author of the now-described “cult classic”, ‘Caliban and the Witch’. It started as a pair of essays in the 1980s and was first published as a standalone book in 2004. Since then, it’s had some light revisions across later editions and translations, but, Voltmer says, it has been “unaffected by 40 years of new scholarship”. The problem is, it should have been affected.

In brief (as Voltmer summarises in her article): in ‘Caliban and the Witch’, Federici presents the witch hunts as an international conspiracy by state and church to destroy women’s liberty, their knowledge about nature, abortion, birth control, and magic, and their free sexuality. The underlying agenda was to reduce women to child bearers and raisers to populate the work and military forces of Europe. (There are a few more angles to it, but these are the relevant ones for our purposes.)

“In the 1980s, Federici’s approach was excusable, because witchcraft research was still in its infancy,” Voltmer writes, “However, during the years to come, Federici did not distance herself from these misconceptions, since otherwise her entire theory […] would have collapsed.”

What do we know now?

What’s agreed today (while acknowledging that figures vary greatly across time and place) is that around 50-60,000 people in Europe were executed as witches during the 15th to 18th centuries, and around 75-80% of those people were women.

And while Alison Rowlands has said that “we must accept the fact that the patriarchal organisation of early modern society was […] a necessary precondition for witch-hunts that produced predominantly female victims”, we cannot accurately say it was a case of church/men against women, or even against a particular age, class, or vocation of women.

Research shows, for example, that there was no organised conspiracy (hotspots of persecution, and the pipeline of witch trials to higher courts, were frequently small and/or rural jurisdictions), it was frequently women who defamed and testified against other women as witches (this was used as a tactic for “resolving everyday conflicts”), and that midwives and women healers were neither usual suspects nor usual victims of witch trials.

Voltmer’s article asks: “Why are the myths about the European witch hunts still to be found in Federici’s writing, long after they have been debunked by historians of the period; and why do so many feminists still believe in these myths today?”

Where did the myths begin?

By the late 17th Century two theories had developed around the cause of the witch hunts. One attributed it to the fanatical fantasies, fears, and phobias of churchmen. The other accepted the reality of magical practice and believed persecution was about either a) eradicating the social danger of magic or b) eradicating powerful and rebellious women.

Federici subscribes to the latter of these two theories.

So too, did two men named Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) and Jules Michelet (1798-1874).

Grimm (yes, he of fairy tales fame) claimed to have discovered evidence that German victims of witch trials had been “wise women”, priestesses of a pagan-folk religion, who practiced medicine and fortune-telling. But his vision of these women, Voltmer says, was shaped by the religious and gender norms of the time. His work was, she says, “essentially anti-feminist”.

Michelet built on Grimm’s theory, claiming the existence of a “healing rebel” whose access to the secrets of nature came via Satan. These women spoke with animals, trees, and clouds, acted as doctors and midwives, and provided contraception and abortions. But again, his vision was shaped by his own beliefs: that women were physically and mentally weak, needed male assistance, and would only find true fulfilment as wives, mothers, and carers.

And here’s where things get challenging for the modern feminist. Voltmer describes how Grimm and Michelet’s creation of the ‘witch’ can be traced through much of what has come since. From the 19th Century American feminist Matilda Joslyn Gage, who is considered the first to express a clearly feminist interpretation of the witch hunts, to England’s Margaret Murray, who claimed to have discovered an underground Pagan witch-cult, which in turn helped inspire Gerald Gardner’s founding of the Wicca movement. And from the second wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 70s, which adopted the witch as a symbolic figure of patriarchal resistance, all the way up to Silvia Federici’s latest edition (2021) of ‘Caliban and the Witch’.

“[H]er version of the conspiracy myths of the witch hunt […] derives, with little modification from ‘dead white men’ such as Grimm and Michelet, and breathes their spirit. Thus, ironically, the antifeminist, indeed explicitly misogynist Michelet has become the godfather of the feminist icon of ‘the witch’,” Voltmer says.

She describes this as a case of Gebrauchsgeschichte or ‘useful history’ – “the political use of historical narratives, myths and even fake news to legitimize one’s own (collective or individual) ideology or interests, without regard for the historical consistency or for the accuracy of the narratives deployed”.

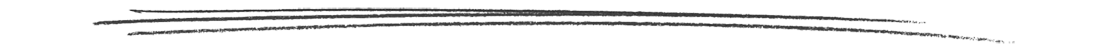

A protest sign I photographed at the 2017 Women’s March on London.

For me, there’s another irony here. Whether knowingly or not, the feminists who, for example, invoked the iconography and practices of the ‘witch’ to protest the presidency and the misogyny of Donald Trump could be said to be employing the same approaches he does. Isn’t Trump’s March 2025 executive order to “restor[e] truth and sanity” to American history by focusing only on the positives of the past and “removing improper ideology”, such as discussions about racism, another form of Gebrauchsgeschichte?

Don’t get me wrong, I have joined these same feminists on protest marches against Trump; I have invoked and celebrated the iconography of the ‘witch’; I have even previously written about (based on an outdated source, and since unpublished) women being targeted during the witch hunts for the nature of their work. As I said at the top – the title of this article is aimed at myself as much as anyone else.

But as Voltmer concludes her own article: “the conspiracy myths advanced by Federici obscure the unpleasant fact that it was not the faceless apparatus of the state and its obedient male agents, but was rather specific named men (and women) who as stakeholders, collaborators, and spectators were responsible for the marginalization, persecution, and extermination of the historical ‘witch’ (women and men alike).” And that “the use of fake history about the witch trials is abusing again and again those women and men who had actually been slandered, tortured, and killed as alleged witches”.

It calls to my mind a plaque unveiled in Orkney, in Scotland, in 2019 dedicated to the at least 72 “innocent people” accused of witchcraft there between 1594 and 1645, which declares: “they weren’t witches, ‘they wur cheust folk’ (‘they were just folk’)”.

Furthermore, Voltmer calls for “more awareness and care” in using the label ‘witch’ – a term that still poses the danger of death to women in some parts of Africa and Asia today.

Resources:

- ‘Memorial for “Innocent” Victims of Orkney Witchcraft Trials Unveiled’, The Scotsman (2019)

- ‘Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History’, The White House, (2025)

- Rowlands, Alison, ‘Witchcraft and Gender in Early Modern Europe’ from The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America, ed. by Brian P. Levak (2014)

- Voltmer, Rita, “Federici’s Witches: Old Male Myths in New Feminist Garb?” in Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft, vol. 20 no. 2, (2025)