A couple of the links/topics I shared in Wednesday’s monthly post (what makes historians go ‘wait, what?’ and ruin lust) had me tangentially thinking about a theme I came across during the archives module for my MA studies.

I’ve written before about the thrilling possibilities of archives and history collections, so it will probably come as no surprise that I feel an affinity with the historians who – as the title of this fortnight’s newsletter suggests – feel a rather strong fondness for archives and the evidence they discover there.

In an article about the role of national archives, Stefan Berger described historians’ interaction with archival sources as “part of a love affair” and working in archives as a “sensual experience”. He said archives’ ability to authenticate and legitimate the work of historians, and their potential to be the source of the “missing link”, leads us to fetishize them.

Indeed, in a paper about Leopold von Ranke (who’s been called ‘the father of the historical discipline’), Kasper Risbjerg Eskildsen shared many of the ways Ranke described his experiences in the Venetian archives in the 19th Century in romantic terms:

- In an 1831 book on the subject, Ranke “not only listed the many documents that one could find on the shelves, but also described the building, the rooms, the light falling through the windows, and the coolness of the air in August”.

- Ranke’s letters about his archival explorations, Eskildsen said, were “sentimental” and “contained the entire register of Romantic emotions and experiences”.

- Ranke sometimes compared himself to “a Romantic explorer”, to Columbus, or at least “a kind of Cook for the many beautiful, unknown islands of world history”.

- To Ranke, archival sources were “treasures”; his discussions of them were “passionate”.

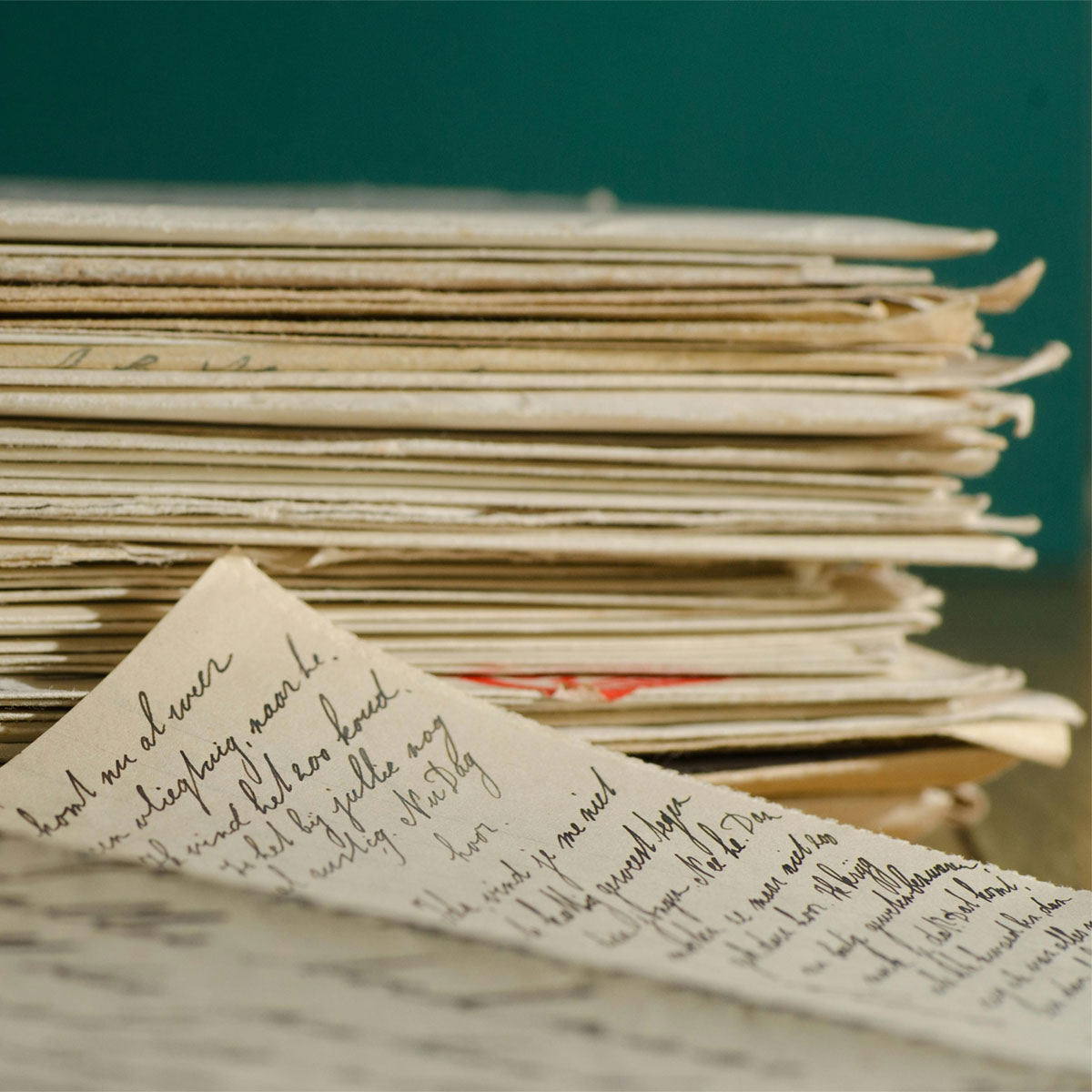

Arlette Farge (celebrated for her ability to read archival sources ‘against the grain’ and unearth evidence of ordinary people’s lives) wrote a book on the subject: ‘The Allure of the Archives’. In it she described her “seduction” by, and the “preciousness” of, old manuscripts; she wrote of the “physical pleasure” of finding traces of the past and that “archival discoveries are a manna”. Farge’s book takes the reader into the archive with her, helping us imagine not only the feel of the documents she’s touching, but the emotional experience of her research.

In the foreword to the English translation, Natalie Zemon Davis reflected on her own experience of that tangibility and emotion: “I still recall the look of the important archival sources I’ve used: the large heavy volumes, their leather thongs and sometimes their original bindings; the bundles of papers tied with string, sometimes with a centuries-old pin holding pages together. In their handwriting, their occasional doodles and asides, and their registers, I have in my hands a link to persons long dead.”

The flipside to this adoration, however, is that archives can’t love us back. They will disappoint us and break our heart as often as they make it swell.

Lisa Jardine straddled these highs and lows in the title essay from her collection, ‘Temptation in the Archives’. She described it as “a cautionary tale about the trust we historians place in documents and records, and how badly we want each precious piece of evidence to add to the historical picture”. The essay follows “a paper-chase” from archive to archive, and through the work of past historians; years of “effort and anticipation” in search of a 17th Century letter. Along the way Jardine develops a suspicion that her longed-for evidence has been “tampered with”, hidden from easy rediscovery. When (spoiler alert!) she eventually, “triumphantly”, locates the letter, it “failed to live up to its promise”, or, at least, her original expectations. But while it didn’t provide the desired insight on the letter writer, it did, however, pique Jardine’s interest in the lives of two other people mentioned in the letter, setting her off on new archival adventures.

In the book ‘The Silence of the Archive’, Valerie Johnson reflected on Jardine’s essay and the “siren call” of the archive; the “longing” of historians to find the key piece of evidence that will unlock their investigation. But, she said, due to the inherent silences in the archive – “created where records have not been kept, deliberately or otherwise; where some voices have been privileged over others; where voices have been silenced” – the “hoped-for Eureka moment” may never come. “Sometimes the hard truth is that the evidence is not, and never was, there.”

Despite this, historians’ curiosity and detective tendencies prevail. Hope and love continue to triumph over the fear of disappointment and heartbreak; historians continue to search archives and – particularly important for those of us who focus on women’s history – examine sources in creative ways to reveal hidden histories.

As Alexandra Walsham has written, researchers of marginalised people and communities have “become particularly adept at reading the gaps and silences in sources” and (as demonstrated by Farge, for example) have “shown how administrative records can be prized open to reveal the voices and actions” of those most under-represented in the archive.